Rumble Pie #7

Tree Tenancy & the Future of Roofs

IN THE CURRENT political climate, there is a tendency to herald every baby step taken in the general direction of sustainability as a giant leap for humankind. Sure, it is important to give positive reinforcement to young children when they achieve even modest accomplishments. But we are not children! We may be acting like spoiled children, despoiling the environment for our own short-term convenience, without a thought for the long-term consequences. But we have the mental acumen of full-grown adults, and we can no longer claim ignorance of the ecological emergencies in this day and age. So let's be a bit more humble about our tiny triumphs and encourage each other to strive higher. Let's not compare ourselves to ecological laggards -- but to environmental visionaries like Freidensreich Hundertwasser.

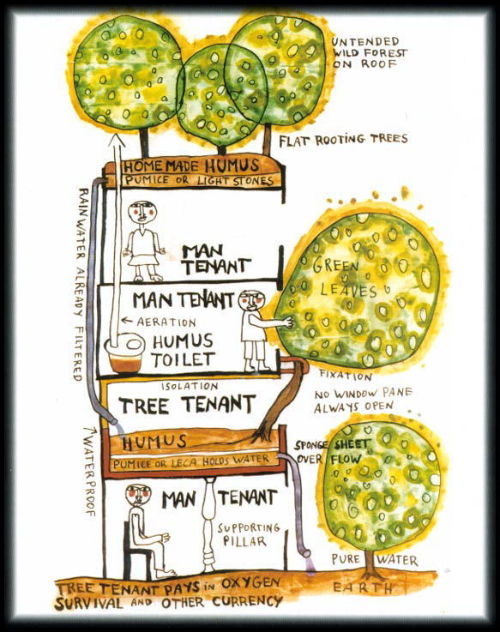

NEARLY SIXTY YEARS AGO, Hundertwasser began formulating his philosophy of roof reforestation. It took him a full five decades to realize his dream, but by time of his passing at the turn of the millennium, several cities in Germany and Austria had graced their skylines with his magnificent tree temples. At street level, his buildings don't blend into the background because they're bright and colourful, but from an eye-in-the-sky perspective, their topographic appearance is completely green. Hundertwasser didn't pot plants into concrete cubes, he stuffed housing under bushy turf and leafy trees -- hundreds of them! He considered it his human duty, even appropriating apartments within the buildings for 'tree tenants' that cantilever their canopies out the upper-floor windows. Hundertwasser's houses are hyper-futuristic -- if you believe that future is something worth fighting for.

HUNDERTWASSER'S MORTAL ENEMY was the right angle. His first manifesto, published in 1953, was entitled 'The Straight Line Leads to the Downfall of Humanity' (La ligne droite conduit a la perte de l'humanite). He proclaimed, "The eyes' nervous system perceives the infinite number of straight lines as acute dangers. Man grows mentally ill without knowing why." Chinese feng shui practitioners, anthroposophic interior designers, and most modern environmental psychologists would agree. Hundertwasser applied this philosophy to all three spatial dimensions, undulating not only a building's walls and windows, but its floors, as well -- "An uneven floor is a melody to the feet", he asserted with typical aplomb, "Flat floors are good for machines, good for dictators -- not human beings."

HIS REVULSION FOR all things rectilinear extended even to the fourth dimension, time. Buildings, he believed, should not remain constant, but instead morph from moment to moment. "We should be glad when rust settled on a razor blade, when a wall grows moldy, or when moss grows over the geometric angles of a corner, because, together with microbes and mushrooms, life thus moves into a house and through this process we more consciously become witnesses of the architectural changes from which we must learn." Predicting the field of biomimetics a half-century before it became a meme, Hundertwasser felt that the best examples of engineering occur where an edifice degrades and non-human nature reclaims the man-made environment.

HUNDERTWASSER WAS so far ahead of his time, that just in order to get noticed, he would have to be radically theatrical. During a university campus speaking tour in the 1960s in which he fearlessly promoted composting toilets (which he later named the Sacred Shit Manifesto), in order to underscore his contempt for contemporary architecture, he would launch paint projectiles at the surrounding structures, and strip naked for added emphasis! Asked if he saw himself as a good architect, he quipped, "No, I don't... But the others are so bad!" Inevitably, the police would arrest him for creating a public nuisance. In his defense, he would cite Saint Francis of Assisi, the patron saint of animals and the environment, who purportedly would also preach in public without any clothing on.

HUNDERTWASSER WOULD claim that clothing is a person's second skin, and housing is their third skin. When the emperor has no clothes, sometimes you have to take off your own just to draw attention to that fact. So he removed his own secondary stratum to draw attention to the paucity of our tertiary layer. And this he did out of love for our shared humanity, not for his own personal benefit. When the spirits moved him (and they often did), he donated his drafting skills on a pro bono basis. It was well worth it to design a healthy house for free, he felt, if it would "prevent something ugly from going up in its place". If, in his own place, another dozen Hundertwassers had sprouted out, we would see a real ecological leap forward in our time. And if we could co-create a culture that nurtured a hundred Hundertwassers, then we would truly deserve a collective pat on the back!

|